Frances Perkins and the Movement for Social Rights

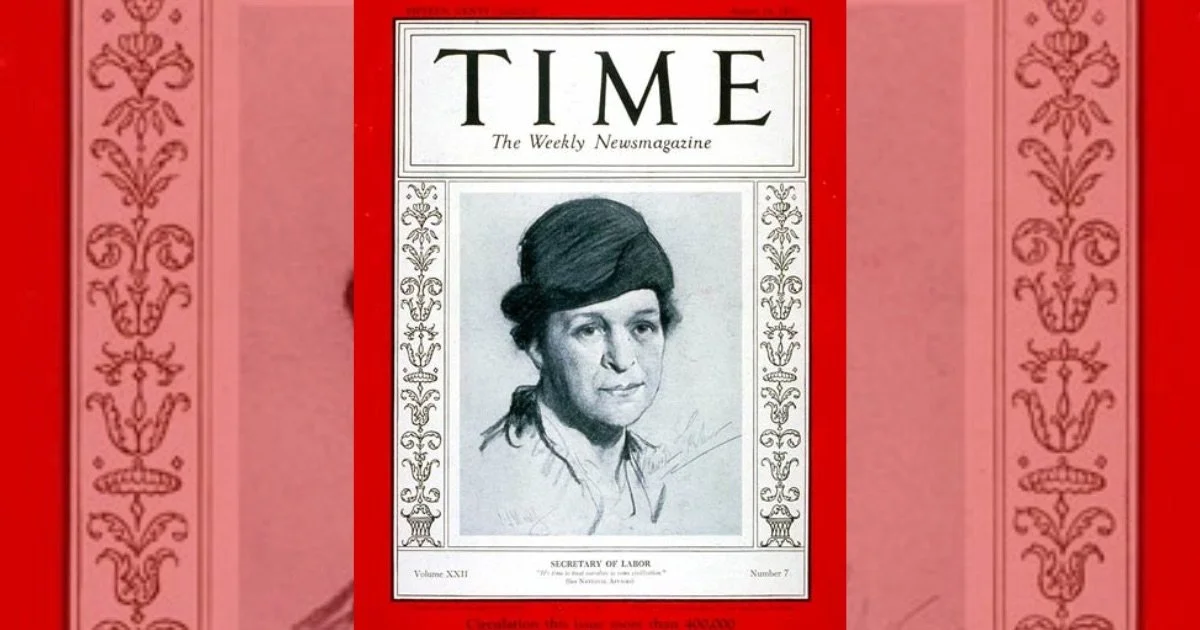

It seems that we sometimes forget the long struggle and the hard-won gains of the social rights movement. Although these rights were not always called “social rights,” the protections Americans count on for our health, families, children, and jobs were championed by early twentieth-century movements that women often led. In the 1930s, Frances Perkins (1880-1965), the first female Cabinet member, played a crucial role in finally enacting many of these rights.

In 1948, Eleanor Roosevelt led the UN committee that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). As a champion for human rights, ER also played a key role in convincing both the international community and the US to expand its concept of human rights to include economic, social, and cultural rights. In 1966, the UDHR was split into the binding language of two international treaties: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights.[1] One hundred seventy-one countries signed and ratified the Covenant, and as a result, social and economic rights became law in many countries. The US is one of four countries that signed but did not ratify it, but even without ratification, social and economic rights have become embedded in US federal and state laws.

As called for in the UN Covenant, social and cultural rights include protection of and assistance to families, support for mothers before and after birth, prohibitions on child labor, rights to education and healthcare, and protections for women and children from economic and social exploitation. Economic rights refer to people’s rights to make a decent living for themselves and their families, and they include fair wages, safe working conditions, limits on working hours, the right to form unions, and the right to rest and leisure. Today, scholars refer to social and economic rights as those allowing individuals to support themselves and live a life of dignity.

Many early twentieth-century reformers, like Florence Kelley and Jane Addams, worked tirelessly toward what we now call social and economic rights. Coalitions of women’s networks, social work groups, consumer groups, and labor union leaders struggled for over forty years for federal legislation for labor safety standards, minimum wage, eight-hour workdays, and the abolition of child labor. Unfortunately, the courts often overturned the laws when they achieved legislative progress toward those rights. For example, in 1916, Congress used the constitutional federal authority over interstate commerce, as laid out in the Commerce Clause, to pass the Keating-Owen Act that outlawed interstate commerce of goods produced by child labor. In June 1918, the US Supreme Court declared the law unconstitutional by a five to four margin in Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 US 251. The subsequent 1919 Child Labor Tax Law, which taxed goods produced with child labor, was in place for three years until May 1922, when the US Supreme Court overturned it in Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Company, 259 US 20. A constitutional amendment that would give Congress the authority to limit child labor passed but was never ratified by the states. It wasn’t until the 1930s, and the work of FDR and Frances Perkins, that the legal and legislative systems turned toward federal social rights.

Frances Perkins served as Secretary of Labor under FDR for twelve years. She was the creative and administrative force behind many New Deal social rights policies, like Social Security and the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938. These bills instituted federal policies that had been the focus of women social reformers for decades. While the competing values of individualism and community caring both had long traditions, the rights of individuals and commerce dominated political and legal policies. Perkins was the leader of a 1930s political movement that changed that. Perkins acted upon the values she had developed while working with the social rights movement, particularly with her mentors, Jane Addams and Florence Kelley, and working with colleagues such as Grace Abbott.

As a young woman, after living and working at Addams’s Hull House settlement in Chicago and then fighting sex trafficking in Philadelphia, Frances Perkins moved to New York for graduate work at Columbia University. After graduation, she became the head of the New York Consumers League. Witnessing the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911 changed her life trajectory. She saw workers, primarily recent Italian and Jewish immigrant women between the ages of 14 and 23, jumping to their deaths to avoid the flames. Locked factory doors prevented escape, and fire department ladders did not reach their floors. A total of 146 people died. After witnessing that horror, Perkins dedicated her life to industrial reform. With Teddy Roosevelt’s recommendation, she became the executive director of the newly created New York Committee on Safety. Her innovative work led to an appointment with the NY State Industrial Commission, and FDR made her the first female New York State Industrial Commissioner.

In 1933, FDR summoned Perkins to discuss a possible appointment to his cabinet. She came with a hand-written list of ideas and priorities she had developed over her years of work in the labor and reform communities. She later said that when FDR campaigned for a “New Deal,” it was just “a happy phrase” and that he had no clear plan of action to fix the social and economic crisis of the Depression. In 1933, 25 percent of the US workforce was unemployed. With her labor and social reform background, Perkins had ideas about experimental ways to address these problems.

She told FDR that he would not want her as Secretary of Labor unless he were willing to support specific initiatives. She laid out a plan with the following goals: 1) Address unemployment through a general works program; 2) Create federal child labor laws to get children back in school and support adult employment; 3) Establish maximum workday hours; 4) Set a federal minimum wage based on a living wage; 5) Support workers’ compensation programs and unemployment insurance programs; 7) Establish safety regulations in the workplace; 8) Find a way to support old-age workers through an insurance or pension plan. FDR was most reluctant about the last goal but agreed to her conditions.[2] In accepting his nomination, she became the most powerful woman in the federal government.

In June 1934, FDR acted on his promise to Perkins to support an old-age pension. He created the Committee on Economic Security, a cabinet committee with Perkins as chair. He gave them the responsibility to develop a social security plan but allocated no funds to work with during the planning process. Further, he insisted that the program could not cost the government any money. FDR also created a larger citizens committee, the Advisory Council to the Committee on Economic Security, to gather data and assist the cabinet committee in drafting a proposed plan.

After six months of research, in December 1934, the cabinet committee met at Perkins’s home to hammer out a final plan. Perkins ushered the small group into her dining room, placed a bottle of scotch on the table, and told them they would not leave until they had a plan. Within six hours, the cabinet committee had agreed on a draft plan, utilizing the reports and plans generated by various groups and committees. Previous decades of persistent social rights advocacy, research, and experimentation were critical to the committees’ ability to create a comprehensive plan quickly. Perkins submitted to the president the following day.

In January 1935, FDR publicly called for Social Security legislation, and on that same day, two congressmen introduced the bill in Congress. Its primary measures were old-age insurance benefits for most industrial workers, unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation for industrial accidents, a program of aid to dependent mothers and children, and assistance to blind people and those with disabilities. After negotiations and compromise, Congress passed the final law in August 1935, signed by FDR. The law included the federal insurance plan we know as Social Security and grants to states for programs like unemployment insurance. A significant disappointment to Perkins was the elimination of national health insurance from the bill. Although health insurance had early support in Congress and from FDR, others, like the American Medical Association (AMA), mounted a successful lobbying campaign against it.

While the Social Security Act created support systems now termed social rights, the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) enacted many of Perkins’s goals for workers, including many of the economic rights described by the later UN covenant. It required a 44-hour work week, followed by reductions down to a 40-hour work week within two years. It also set minimum wages, established overtime wage requirements, and, finally, outlawed child labor under age 16 for most non-agricultural work. The FSLA was challenged before the Supreme Court in 1941 but was finally upheld in US v. Darby. The Court’s unanimous decision held that Congress could enact laws concerning fair labor practices, including restricting child labor.

Perkins helped create legislation that still influences our lives today. She championed the American tradition of caring for each other through laws protecting workers and establishing the social rights safety nets we all rely upon. Her story helps us remember how important it is to have women at the table for policy decisions.

[1] United Nations. International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, 1966. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-economic-social-and-cultural-rights

[2] Perkins described this dialogue with FDR in her oral history, Part 3, p. 594. http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/collections/nny/perkinsf/transcripts/perkinsf_1_1_1.html

Judy Whipps is Professor Emerita of Philosophy and Interdisciplinary Studies at Grand Valley State University.

Related Essays